The Governance of Prevention in Germany

Paglione L,* Baccolini V,* Marceca M,* Villari P*

*Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza - University of Rome

Edited by: L. Palombi, E. De Vito, G. Damiani, W. Ricciardi

The Federal Republic of Germany has maintained its organisation based on the solidarity principle since its introduction in 1883. Indeed, Bismarck's Health Insurance Law adopted in 1883 established the first social health insurance system in the world to which insured people (an estimated 10% of the total population) contributed through a percentage of their income. They were mainly blue-collar workers (in salt works, processing plants, factories, metallurgical plants, railway companies, shipping companies, shipyards, building companies). From that point, coverage was continuously expanded to large sections of the population, e.g. students and farmers, until the 1960s and 1970s. This gradual expansion of coverage in terms of population and benefits has led to what is, in 2017, universal health coverage with a generous benefits package.

There are three key elements of Statutory Health Insurance (SHI): first, according to the principle of solidarity, the amount of the insurance contributions is based on ability to pay; in turn, the insured individual is entitled to benefits according to need. Second, statutory health insurance is compulsory insurance in which employers take part in the financing. Finally, statutory health insurance is based on self-governing structures, which means that competencies are delegated to membership-based, self-regulated organisations of sickness funds and health-care providers.1

Organisation of Prevention Services

The organisational structure of prevention services in the Federal Republic of Germany is divided into multiple levels that reflect the country’s administrative and political structure. This system is the result of a number of reforms that started in the 1970s, where various attempts were made to reorganise public health services. Originally, public health services included immunisations, mass screening for tuberculosis and other diseases, as well as health education and counselling. Since the 1970s, however, many of these individual prevention services have been transferred to physicians in private practice, combined with an expansion of the Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) benefits package.2

Actually, before 1970, only antenatal care was included in these benefits packages. Since 1971, however, some changes have taken place as part of a process of reorientation within public health services towards population health compared to the widespread patient-oriented medical perspective. Screening for cancer has become a benefit for women over 20 years and men over 45 years. At the same time, regular check-ups for children under 4 years of age were introduced (and extended to children under 6 years of age in 1989 and to adolescents in 1997). Primary prevention and health promotion were made mandatory for sickness funds in 1989, eliminated in 1996 and reintroduced in modified form in 2000.

From 2000 to 2010, spending on primary prevention increased from €1.10 to €4.33 per person covered by SHI. In 2010, around 12 million people – many more than in the previous year – received prevention and health promotion activities from their sickness funds. Setting-based measures were expanded. In 2010, more than 30,000 institutions – especially kindergartens, schools and vocational schools – were supported by targeted activities in the areas of exercise and healthy eating, thereby reaching 9 million people.3

The growth of the SHI benefits package to include screening and early detection services means that private-practice physicians are obliged to deliver these services as part of the regional budgets negotiated by the regional associations of SHI physicians and the health funds. For some other services, such as immunisations, the physicians negotiate with the health funds and arrange separate fees that are not part of the regional budgets. Consequently, prevention services are now delivered within the same legal framework as curative services, meaning their exact definition is subject to negotiation at federal level between the health funds and the physicians.

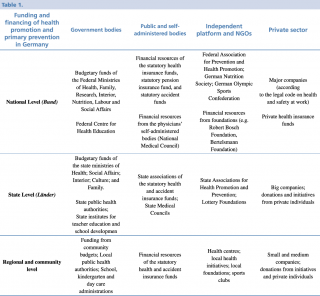

Prevention, therefore, is modelled on the political structure of the country and based on the Bismarckian corporate welfare state. It is included in public health services that recognise authorities at national, state and municipal level. The legislative responsibility for most policy areas is divided between national and federal authorities. Key players are government organisations, self-administered bodies and non-government organisations, which are part of an effective network that shares responsibilities and duties. Accordingly, policies, health promotion and primary prevention implementation measures are introduced and developed at different levels and in two areas – within government organisations, non-government organisations and self-administered bodies.

Germany’s federal structure ensures that the federal states (Länder) have minimal involvement in setting up and running prevention services. Actually, the 2006 Federalism Reform legally defined the transfer of responsibilities from national level via state level to local level, where local health authorities and public health departments share responsibilities including health protection, management and prevention.4

Federal level

The 2013 coalition agreement provided key aspects of a legal draft for a federal law on prevention and health promotion to strengthen interventions in settings such as schools, kindergartens, day care facilities, chronic care and nursing homes and companies. Indeed, the Federal Ministry of Health is responsible for the control and prevention of infectious diseases and preventive healthcare, and for devising strategies and policies on prevention, rehabilitation and disability.

State level

The 16 states (Länder) have legal responsibility for providing health services and each of them follows its own approach for prevention and health promotion. Most of the states have implemented associations for health promotion and prevention (Landesvereinigung für Gesundheit), which include stakeholders from all spheres and multilateral funding of health promotion measures.

Local level

In many federal states, prevention services are devolved to municipal level. This “municipalisation” of health authorities has resulted in the creation of better conditions for integrating prevention services into the municipal health policy process. Depending on the federal states, there are also various specialised authorities and state agencies that are part of the public health services. Therefore, local health authorities or public health departments have the political responsibility for the health of the population in their communities.

Delivery of Healthcare Services

The German healthcare system is based on the principle of subsidiarity. Regarding the provision of prevention services, this principle is reflected directly in the presence of a network of social and health services. In this way, the various administrative levels can coordinate with each other effectively, and the result is a complex network of financing organisations and providers. Each of these contributes to providing services, which are however coordinated with all other actors. A fundamental role is played by the primary care service, which effectively combines prevention and health promotion through the implementation of programmes such as vaccination and screening, but also through coordination with primary schools and non-profit organisations.5

- Federal government level (Bund): health promotion and prevention campaigns are planned by the Federal Centre for Health Education (Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, BZgA), an agency under the direct responsibility of the Federal Ministry of Health. The central level has the main objective of planning actions and providing a framework within which to implement prevention programmes.

- State government level (Länder): the State Associations for Health Promotion and Prevention develop strategies and concepts. These institutions aim to provide a bridge between the policy sphere and the practical actors, to organise and coordinate the various stakeholders in prevention networks, joint actions, and projects. Regional institutions therefore have a role of coordination of the various actors who are immediately below them, without providing the service directly but providing for forms of monitoring and evaluation of expenditure.

- Self-administered bodies: prevention guidelines are developed and disseminated by the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds. Another example is the development and dissemination of guidelines for practical and clinical aspects of disease-specific prevention by the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF).

- All levels: the National Health Targets Process applies a participatory approach by bringing stakeholders from all areas together to achieve defined health targets for primary prevention.

Financing of Prevention Services

As described for the delivery of healthcare services, funding is within the complex organisational network, with a similar complexity of income sources and expenses. Because the service is composed of a range of different actors on different levels and in different legal frameworks (public bodies, institutions, private associations, public and private insurance), it is difficult to establish precisely the amount of resources for each individual prevention service. In 2012, the total costs for health services in Germany were just above €300 billion, of which 3.6% (€10.9 billion) were invested in prevention. Sources of funding are divided into levels, which finance all activities included in the planning of each institution. The following picture (BZgA - CHRODIS, 2015 – 5) effectively illustrates the flows and the connection points for each level of funding.

Workforce

The German health system has a structure that is widespread and divided into various branches, but is not well-defined. Many employees are involved in maintaining and promoting health without being strictly related to the health sector, and since health promotion is effectively entrusted to "third parties", like schools or community networks, it becomes difficult to obtain data on the real workforce involved in prevention services. The accuracy of the financing flows, and the guarantee that each subject, under the control of the Länder, carries out the work for which it has been delegated and financed, allow the system to withstand external pressures, but also to respond effectively to the health needs of the population (responsiveness), through dynamic adaptations and temporary expansions of the workforce.

Conclusions and Outlook

German prevention services are strongly rooted in communities and territories through branches that spill over the boundaries of the Health Service itself. This is the result of a Bismarckian setting of the financing model in combination with a state-based federal organisation that includes well-defined roles and tasks. The good level of coordination among institutions and the third sector of profit and non-profit organisations alongside local communities represent key elements that allow this country to deal effectively with the health needs of the population. The integrated view of social and physical health ensures the proper functioning of the health system in relation to health prevention promotion. Additionally, the complex administration guarantees stability and sustainability for the whole system. By contrast, the fairness and the responsiveness of the service is guaranteed by the considerable diffusion of horizontal health programmes organised and managed locally, but financed in particular by the Länder.

References

- Busse R, Blümel M, Knieps F, Bärnighausen T. Statutory Health Insurance in Germany: A Health System Shaped by 135 Years of Solidarity, Self-Governance, and Competition. Lancet. 2017; 390:882–897.

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Health System in Transition, Germany Health System Review Vol.16 No.2, 2014.

- German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, acatech – National Academy of Science and Engineering and Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities (2015): Public Health in Germany – Structures, Developments and Global Challenges.

- Organisation and Financing of Public Health Services in Europe: Country Reports. Vol. no. 49, 2018.

- Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA), Joint Action on Chronic Diseases, CHRODIS, Germany Country Review, 2015.